So a while ago I got into a discussion with someone on Twitter about whether emojis have syntax. Their original question was this:

do emoji have grammar/direction? if english is 👩📸👨 (girl photographs boy), is arabic 👨📸👩 or 👨👩📸 ? and is japanese 👩👨📸 ?

— r12a (@r12a) November 14, 2016

As someone who’s studied sign language, my immediate thought was “Of course there’s a directionality to emoji: they encode the spatial relationships of the scene.” This is just fancy linguist talk for: “if there’s a dog eating a hot-dog, and the dog is on the right, you’re going to use 🌭🐕, not 🐕🌭.” But the more I thought about it, the more I began to think that maybe it would be better not to rely on my intuitions in this case. First, because I know American Sign Language and that might be influencing me and, second, because I am pretty gosh-darn dyslexic and I can’t promise that my really excellent ability to flip adjacent characters doesn’t extend to emoji.

So, like any good behavioral scientist, I ran a little experiment. I wanted to know two things.

- Does an emoji description of a scene show the way that things are positioned in that scene?

- Does the order of emojis tend to be the same as the ordering of those same concepts in an equivalent sentence?

As it turned out, the answers to these questions are actually fairly intertwined, and related to a third thing I hadn’t actually considered while I was putting together my stimuli (but probably should have): whether there was an agent-patient relationship in the photo.

Agent: The entity in a sentence that’s affecting a changed, the “doer” of the action.

- The dog ate the hot-dog.

- The raccoons pushed over all the trash-bins.

Patient: The entity that’s being changed, the “receiver” of the action.

- The dog ate the hot-dog.

- The raccoons pushed over all the trash-bins.

Data

To get data, I showed people three pictures and asked them to “pick the emoji sequence that best describes the scene” and then gave them two options that used different orders of the same emoji. Then, once they were done with the emoji part, I asked them to “please type a short sentence to describe each scene”. For all the language data, I just went through and quickly coded the order that the same concepts as were encoded in the emoji showed up.

Examples:

- “The dog ate a hot-dog” -> dog hot-dog

- “The hot-dog was eaten by the dog” -> hot-dog dog

- “A dog eating” -> dog

- “The hot-dog was completely devoured” -> hot-dog

So this gave me two parallel data sets: one with emojis and one with language data.

All together, 133 people filled out the emoji half and 127 people did the whole thing, mostly in English (I had one person respond in Spanish and I went ahead and included it). I have absolutely no demographics on my participants, and that’s by design; since I didn’t go through the Institutional Review Board it would actually be unethical for me to collect data about people themselves rather than just general information on language use. (If you want to get into the nitty-gritty this is a really good discussion of different types of on-line research.)

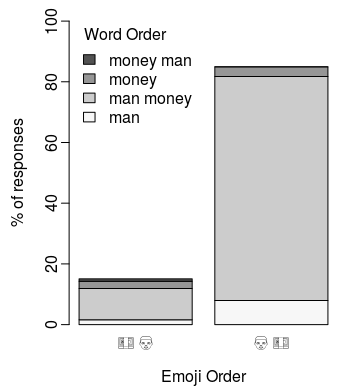

Picture one – A man counting money

I picked this photo as sort of a sanity-check: there’s no obvious right-to-left ordering of the man and the money, and there’s one pretty clear way of describing what’s going on in this scene. There’s an agent (the man) and a patient (the money), and since we tend to describe things as agent first, patient second I expected people to pretty much all do the same thing with this picture. (Side note: I know I’ve read a paper about the cross-linguistic tendency for syntactic structures where the agent comes first, but I can’t find it and I don’t remember who it’s by. Please let me know if you’ve got an idea what it could be in the comments–it’s driving me nuts!)

And they did! Pretty much everyone described this picture by putting the man before the money, both with emoji and words. This tells us that, when there’s no information about orientation you need to encode (e.g. what’s on the right or left), people do tend to use emoji in the same order as they would the equivalent words.

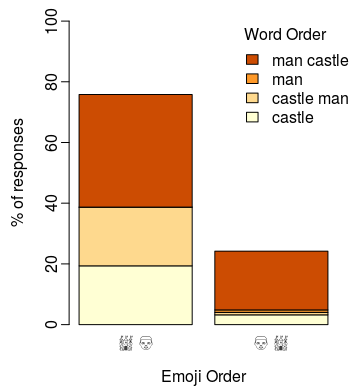

Picture two – A man walking by a castle

But now things get a little more complex. What if there isn’t a strong agent-patient relationship and there is a strong orientation in the photo? Here, a man in a red shirt is walking by a castle, but he shows up on the right side of the photo. Will people be more likely to describe this scene with emoji in a way that encodes the relationship of the objects in the photo?

I found that they were–almost four out of five participants described this scene by using the emoji sequence “castle man”, rather than “man castle”. This is particularly striking because, in the sentence writing part of the experiment, most people (over 56%) wrote a sentence where “man/dude/person etc.” showed up before “castle/mansion/chateau etc.”.

So while people can use emoji to encode syntax, they’re also using them to encode spatial information about the scene.

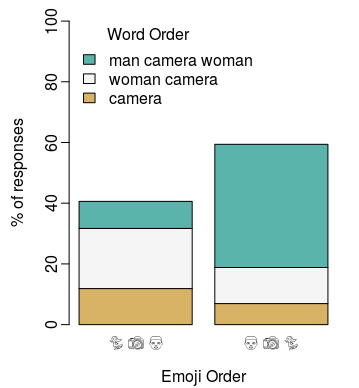

Picture three – A man photographing a model

Ok, so let’s add a third layer of complexity: what about when spatial information and the syntactic agent/patient relationships are pointing in opposite directions? For the scene above, if you’re encoding the spatial information then you should use an emoji ordering like “woman camera man”, but if you’re encoding an agent-patient relationship then, as we saw in the picture of the man counting money, you’ll probably want to put the agent first: “man camera woman”.

(I leave it open for discussion whether the camera emoji here is representing a physical camera or a verb like “photograph”.)

So people were a little more divided here. It wasn’t quite a 50-50 split, but it really does look like you can go either way with this one. The thing that jumped out at me, though, was how the word order and emoji order pattern together: if your sentence is something like “A man photographs a model”, then you are far more likely to use the “man camera woman” emoji ordering. On the other hand, if your sentence is something like “A woman being photographed by the sea” or “Photoshoot by the water”, then it’s more likely that your emoji ordering described the physical relation of the scene.

So what?

So what’s the big takeaway here? Well, one thing is that emoji don’t really have a fixed syntax in the same way language does. If they did, I’d expect that there would be a lot more agreement between people about the right way to represent a scene with emoji. There was a lot of variation.

On the other hand, emoji ordering isn’t just random either. It is encoding information, either about the syntactic/semantic relationship of the concepts or their physical location in space. The problem is that you really don’t have a way of knowing which one is which.

Edit 12/16/2016: The dataset and the R script I used to analyze it are now avaliable on Github.

I think there may be a greater correlation than what you have concluded.

Think about the disagreement among lexicographiers about word usage. Word usage, like emoji usage, is always in a state of flux. In fact I would say emojis – and their use – are more prone to change than the English language because emojis are used in texts, tweets, and other forms of communication that are more susceptible to being changed more often.

Just my two-cents though. Interesting article, with thought-provoking information.

Very interesting!

❤📖

As for the reference for the cross-linguistic agent-patient order, I would refer you to “Clause Structure” by Elly van Gelderen (2013).

It is a very informative textbook from the scratch.

As for the experiment, some of your explanations refer to passive readings which is hard to account for in simple sentences especially when they are translated from pictures to emojis. Therefore, I would focus on the simplest readings “declarative”.

Thank you for the recommendation! And I think you’re right–for future work I should definitely focus on narrower questions. (And have more stimuli!)

One wrinkle here is that you might not be able to interpret all the emoji responses as complete sentences. They might be noun phrases instead. For example, I’d use “(emoji) money man” to mean “the man who has/counts/works with money,” in contrast with “(emoji) man money” which I’d use to mean “the man has/counts/works with money.”

Good point. I wasn’t really looking at perception of emoji sequences, just production, so there might be effects of how people are perceiving these sequences.

I think your intuitions are really interesting–they do seem to suggest you use emoji ordering to form some sort of constituency structure.

What do you think the results for picture 2 would have been if the man had been located to the left of the castle instead of to the right?

I’d need to run another experiment to verify this, but I think there would have been a tendency to use the other order of emoji. Although, as has been pointed out elsewhere, the man and castle picture in particular is one with a strong figure & ground (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Figure%E2%80%93ground_(perception)) so there might be other factors at play here.

Did you take into account the way in which your experimenters were being presented the pictures in which they were viewing?

Say I am taking part in the experiment and I scroll down on my computer to see the picture from top to bottom.I see that there is a Castle first and a man second, So I register it.

Yet someone else has a computer that day and they are seeing the same picture yet there’s is from left to right.

Do you think your study is subject to fallacy due to some framing error.

That’s definitely a possibility. There’s also a large size difference between the castle and the man, which might also be influencing people. I definitely need more data!