This blog post is more of a quick record of my thoughts than a full in-depth analysis, because when I saw this I immediately wanted to start writing about it. Basically, TikTok is a social media app for short form video (RIP Vine, forever in our hearts) and one of the most popular genres of content is short dances; you may already be familiar with the concept.

HOWEVER, what’s particularly intriguing to me is this sort of video here, where someone creates a tutorial for a specific dance and includes an emoji-based dance notation:

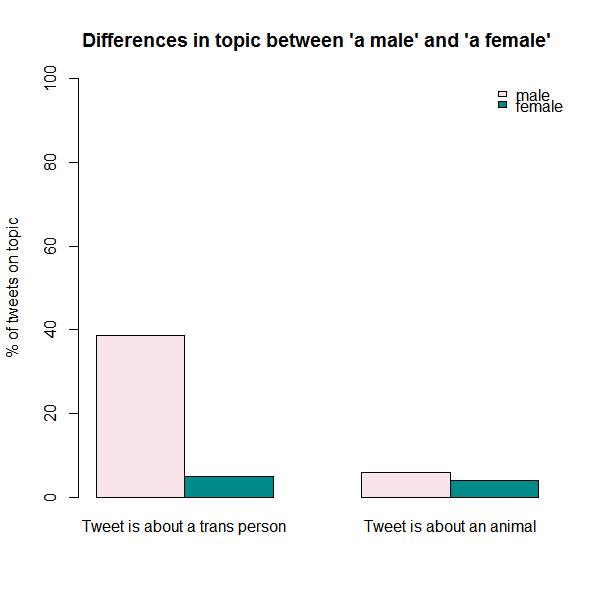

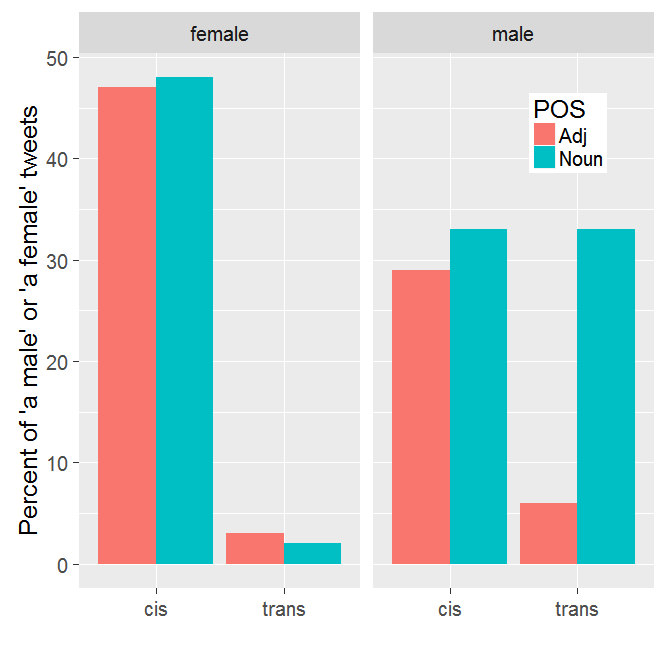

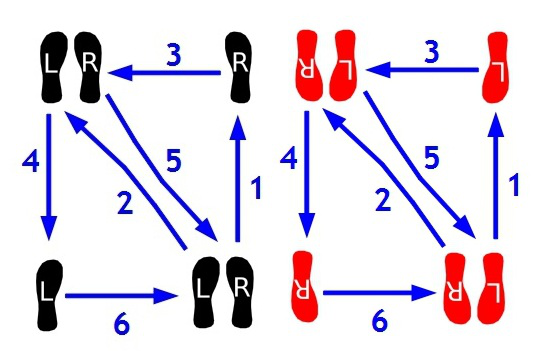

Back in grad school, when I was studying signed languages, I probably spent more time than I should have reading about writing systems for signed languages and also dance notations. To roughly sum up an entire field of study: representing movements of the human body in time and space using a writing system, or even a more specialized notation, is extremely difficult. There are a LOT of other notations out there, and you probably haven’t run into them for a reason: they’re complex, hard to learn, necessarily miss nuances and are a bit redundant given that the vast majority of dance is learned through watching & copying movement. Probably the most well-known type of dance notation is for ballroom dance where the footwork patterns are represented on the floor using images of footsteps, like so:

I think part of the reason that this notation in particular tends to work well is that it’s completely iconic: the image of a shoe print is where your shoe print should go. It also captures a large part of the relevant information; the upper body position can be inferred from the position of the feet (and in many cases will more or less remain the same throughout).

I think that’s true to some degree of these emoji notations as well. The fact that they work at all may be arising in part due to the constraints of the TikTok dance genre. In most TikTok dances, the dancer faces in a single direction for the dance, there is minimal movement around the space and the feet move minimally if at all. The performance format itself helps as well: the videos are short and easy to repeat, and you can still see the movements being preformed in full with the notation being used as a shorthand.

And it’s clear that this use of style of notation isn’t idiosyncratic; this compilation has a variety of tutorials from different creators that use variations on the same style of notation.

Some of the types of ways emoji are used here are similar to the ways that things like Stokoe notation are, to indicate handshape and movement (although not location). A few other types of ways that emoji are used that stick out:

- Articulator (hands with handshape, peach emoji for the hips)

- Manner of articulation/movement (“explosive”, a specific number of repetitions, direction of movement using arrows)

- Iconic representation of a movement using an object (helicopter = hands make the motion of helicopter blades, mermaid = bodywaves, as if a mermaid swimming)

- Iconic representation of a shape to be traced (a house emoji = tracing a house shape with the hands, heart = trace a heart shape)

- (Not emoji) Written shorthand for a (presumably) already known dance, for example “WOAH” for the woah

To sum up: I think this is a cool idea, it’s an interesting new type of dance notation that is clearly useful to a specific artistic community. It’s also another really good piece of evidence in the bucket of “emoji are gestures”: these are clearly not a linguistic system and are used in a variety of ways by different users that don’t seem entirely systematic.

Buuuut there’s also the way that the emojis are groups into phrases for a specific set of related motions, which smells like some sort of shallow parsing even if it’s not a full consistency structure, and I’d say that’s definitely linguistic-ish. I think I’d need to spend more time on analysis to have any more firmly held opinion than that.