The night before last I had the good fortune to see Goeff Pullum, noted linguist and linguistics blogger, give a talk entitled: The scandal of English grammar teaching: Ignorance of grammar, damage to writing skills, and what we can do about it. It was an engaging talk and clearly showed that the basis for many of the “grammar rules” that are taught in English language and composition courses have little to no bearing on how the English language is actually used. Some of the bogeyman rules (his term) that he lambasted included the interdiction against ending a sentence in a preposition, the notion that “since” can only to refer to the passage of time and not causality and the claim that only “which” can begin a restrictive clause. Counterexamples for all of these “grammar rules” are easy to find, both in written and spoken language. (If you’re interested in learning more, check out Geoff Pullum on Language Log.)

Traditional grammar: A variety of usage and style rules that are based on social norms and a series of historic accidents.

Linguistic grammar: The set of rules which can accurately discribe a native speaker’s knowaldge of their language.

I’m not the first person to suggest a linguistics education as a valuable addition to the pre-higher educational experience. You can read proposals and arguments from others here, here, and here, and an argument for more linguistics in higher education here.

So, why would you want to teach linguistic grammar? After all, by the time you’re five or six, you already have a pretty good grasp of your language. (Not a perfect one, as it turns out; things like the role of stress in determining the relationship between words in a phrase tend to come in pretty late in life.) Well, there are lots of reasons.

- Linguistic grammar is the result of scientific inquiry and is empirically verifiable. This means that lessons on linguistic grammar can take the form of experiments and labs rather than memorizing random rules.

- Linguistic grammar is systematic. This can appeal to students who are gifted at math and science but find studying language more difficult.

- Linguistic grammar is a good way to gently introduce higher level mathematics. Semantics, for example, is a good way to introduce set theory or lambda calculus.

- Linguistic grammar is immediately applicable for students. While it’s difficult to find applications for oceanology for students who live in Kansas, everyone uses language every day, giving students a multitude of opportunities to apply and observe what they’re learned.

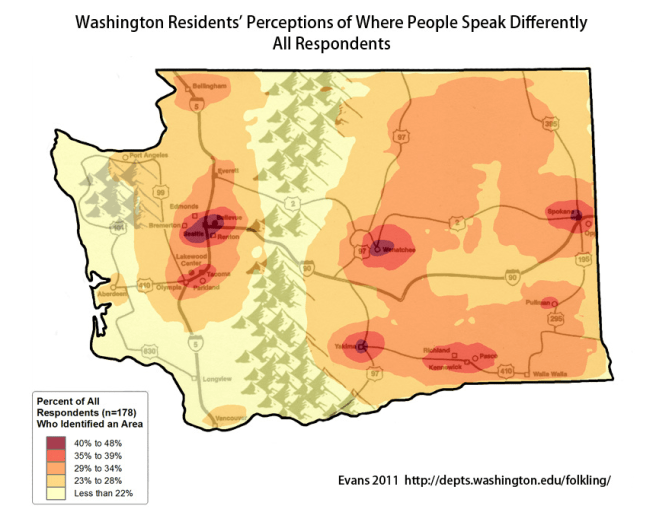

- Linguistic grammar shows that variation between different languages and dialects is systematic, logical and natural. This can help reduce the linguistic prejudice that speakers of certain languages or dialects face.

- Linguistic grammar helps students in learning foreign languages. For example, by increasing students’ phonetic awareness (that’s their awareness of language sounds) and teaching them how to accurately describe and produce sounds, we can avoid the frustration of not knowing what sound they’re attempting to produce and its relation to sounds they already know.

- Knowledge of linguistic grammar, unlike traditional grammar, is relatively simple to evaluate. Since much of introductory linguistics consists of looking at data sets and constructing rules that would generate that data set, and these rules are either correct or not, it is easier to determine whether or not the student has mastered the concepts.

I could go on, but I think I’ll leave it here for now. The main point is this: teaching linguistics is a viable and valuable way to replace traditional grammar education. What needs to happen for linguistic grammar to supplant traditional grammar? That’s a little thornier. At the very least, teachers need to receive linguistic training and course materials appropriate for various ages need to be developed. A bigger problem, though, is a general lack of public knowledge about linguistics. That’s part of why I write this blog; to let you know about what’s going on in a small but very productive field. Linguistics has a lot to offer, and I hope that in the future more and more people will take us up on it.