I’ll admit it: I used to be a die-hard grammar corrector. I practically stalked around conversations with a red pen, ready to jump out and shout “gotcha!” if someone ended a sentence with a preposition or split an infinitive or said “irregardless”. But I’ve done a lot of learning and growing since then and, looking back, I’m kind of ashamed. The truth is, when I used to correct people’s grammar, I wasn’t trying to help them. I was trying to make myself look like a language authority, but in doing so I was actually hurting people. Ironically, I only realized this after years of specialized training to become an actual authority on language.

But what do I mean when I say I was hurting people? Well, like some other types of policing, the grammar police don’t target everyone equally. For example, there has been a lot of criticism of Rihanna’s language use in her new single “Work” being thrown around recently. But that fact is that her language is perfectly fine. She’s just using Jamaican Patois, which most American English speakers aren’t familiar with. People claiming that the language use in “Work” is wrong is sort of similar to American English speakers complaining that Nederhop group ChildsPlay’s language use is wrong. It’s not wrong at all, it’s just different.

And there’s the problem. The fact is that grammar policing isn’t targeting speech errors, it’s targeting differences that are, for many people, perfectly fine. And, overwhelmingly, the people who make “errors” are marginalized in other ways. Here are some examples to show you what I mean:

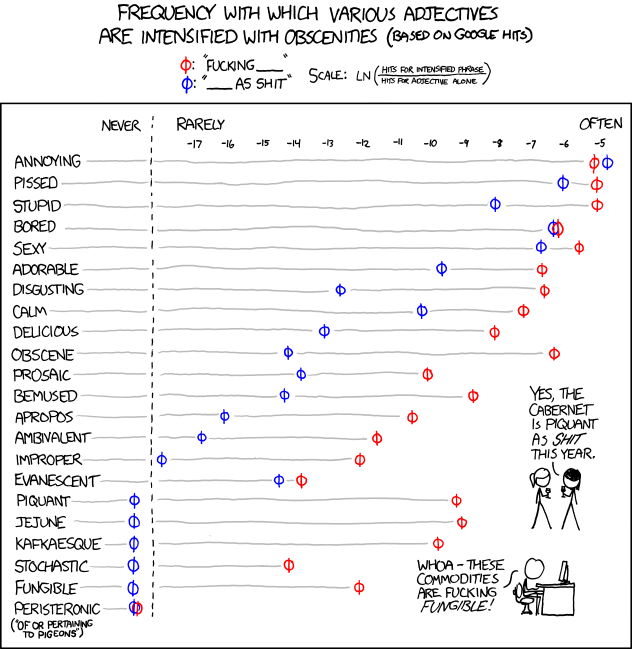

- Misusing “ironic”: A lot of the lists of “common grammar errors” you see will include a lot of words where the “correct” use is actually less common then other ways the word is used. Take “ironic”. In general use it can mean surprising or remarkable. If you’re a literary theorist, however, irony has a specific technical meaning–and if you’re not a literary theorist you’re going to need to take a course on it to really get what irony’s about. The only people, then, who are going to use this word “correctly” will be those who are highly educated. And, let’s be real, you know what someone means when they say ironic and isn’t that the point?

- Overusing words like “just”: This error is apparently so egregious that there’s an e-mail plug-in, targeted mainly at women, to help avoid it. However, as other linguists have pointed out, not only is there limited evidence that women say “just” more than men, but even if there were a difference why would the assumption be that women were overusing “just”? Couldn’t it be that men aren’t using it enough?

- Double negatives: Also called negative concord, this “error” happens when multiple negatives are used in a sentence, as in, “There isn’t nothing wrong with my language.” This particular construction is perfectly natural and correct in a lot of dialects of American English, including African American English and Southern English, not to mention the standard in some other languages, including French.

In each of these cases, the “error” in question is one that’s produced more by certain groups of people. And those groups of people–less educated individuals, women, African Americans–face disadvantages in other aspects of their life too. This isn’t a mistake or coincidence. When we talk about certain ways of talking, we’re talking about certain types of people. And almost always we’re talking about people who already have the deck stacked against them.

Think about this: why don’t American English speakers point out whenever the Queen of England says things differently? For instance, she often fails to produce the “r” sound in words like “father”, which is definitely not standardized American English. But we don’t talk about how the Queen is “talking lazy” or “dropping letters” like we do about, for instance, “th” being produced as “d” in African American English. They’re both perfectly regular, logical language varieties that differ from standardized American English…but only one group gets flack for it.

Now I’m not arguing that language errors don’t exist, since they clearly do. If you’ve ever accidentally said a spoonerism or suffered from a tip of the tongue moment then you know what it feel like when your language system breaks down for a second. But here’s a fundamental truth of linguistics: barring a condition like aphasia, a native speaker of a language uses their language correctly. And I think it’s important for us all to examine exactly why it is that we’ve been led to believe otherwise…and who it is that we’re being told is wrong.