There’s a long-running (and I really mean long-running: Plato chimed in on this one) debate about what language is. Now, as a linguist, you’d think I’d have the inside scoop on the subject. I mean, I pretty much sit around and think about language all day, so I should have this one down cold, right?

Well, as much as I hate to admit it, not really. And it’s not just me. Ask three different linguists what language is and you’ll probably get six to twelve answers. There is one point that I’m firm on, though: language is a human phenomena. Outside of the internet and fantasy worlds (which tend to overlap a lot, now that I think about it), animals don’t talk.

- Lying is part of language. By lying here, I mean a wide variety of linguistic expressions that express information that is counter to the truth, including joking. Language is separate from the things it describes (there’s nothing inherently tree-ish about the word tree, for example, ditto arbor, boom and träd, though there are inherent respect points in correctly identifying all three languages) and because of this can communicate abstract thought. Abstract thought, as evinced through lying, is in inherent part of language. There’s some evidence that Koko the gorilla is capable of lying, but one isolated incident really isn’t a sound basis for scientific argument.

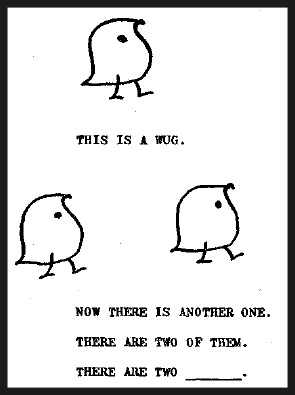

- Language is generative. I’ve written an entire post about generativity, but it’s worth repeating. Language has to have underlying structures that can be used to produce new and novel utterances. Otherwise, you’re just saying random words.

- Langauge is communicative. This is part of the reason why music isn’t language, though it’s completely abstract and (at least in the Western tradition) generative. Abstraction is required, but so is a connection to thoughts and ideas. Tied to this is the fact that you have to have a community to speak in, even if it’s a community of two.

- Language can communicate events at a temporal distance. This is a a biggie, and one of the main reasons that I really think that Koko and other talking animals are really using language. (Quick aside: Did you know that the Nazis attempted to train talking dogs as part of the war effort? True story.) It’s pretty easy to teach a dog to bark for a treat, but try teaching it to bark because you gave it a treat two days ago. You may think that a specific bark means “treat”, but without temporal distance and repeatability, it’s pretty much just pigeons in boxes.

Now, other linguists will take other positions (or, you know, the same position ;), but this is how I see it. So what do you think: can animals talk?